|

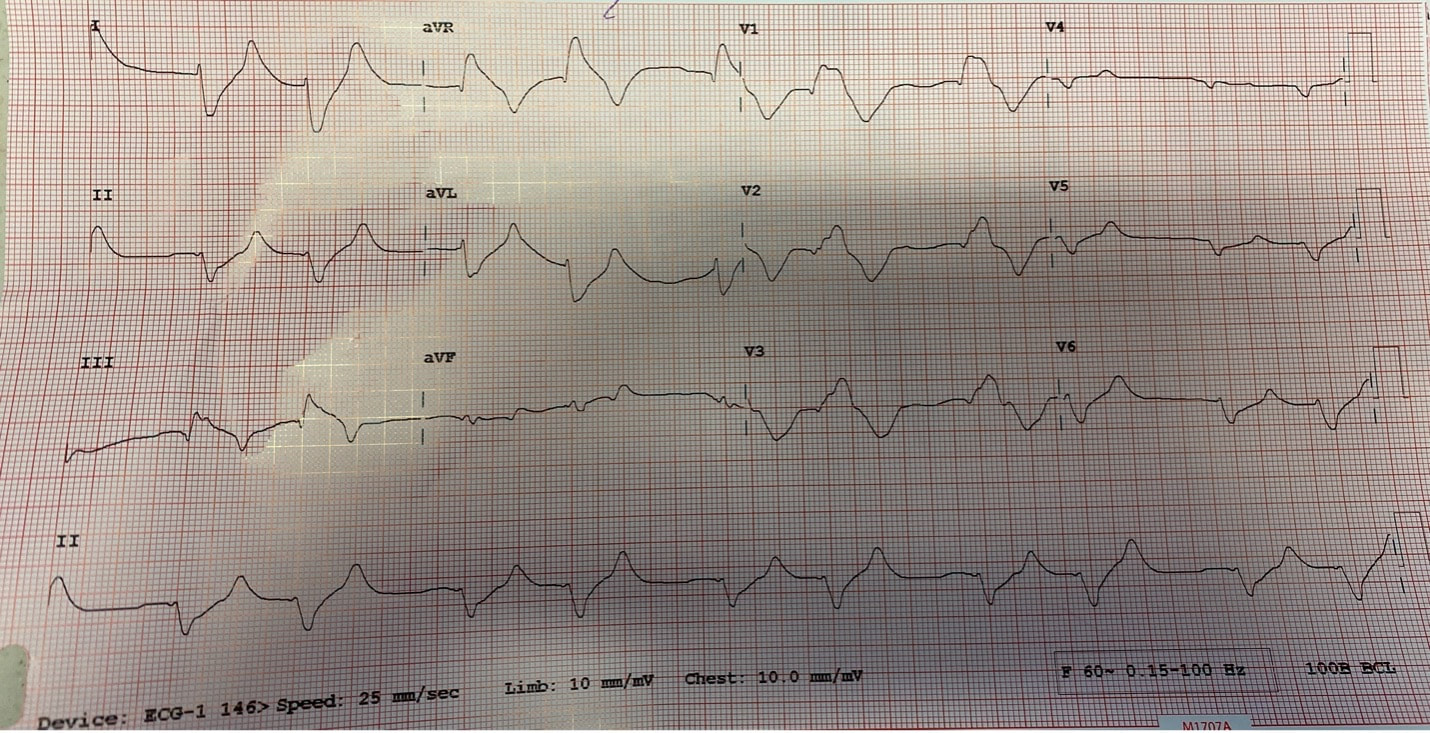

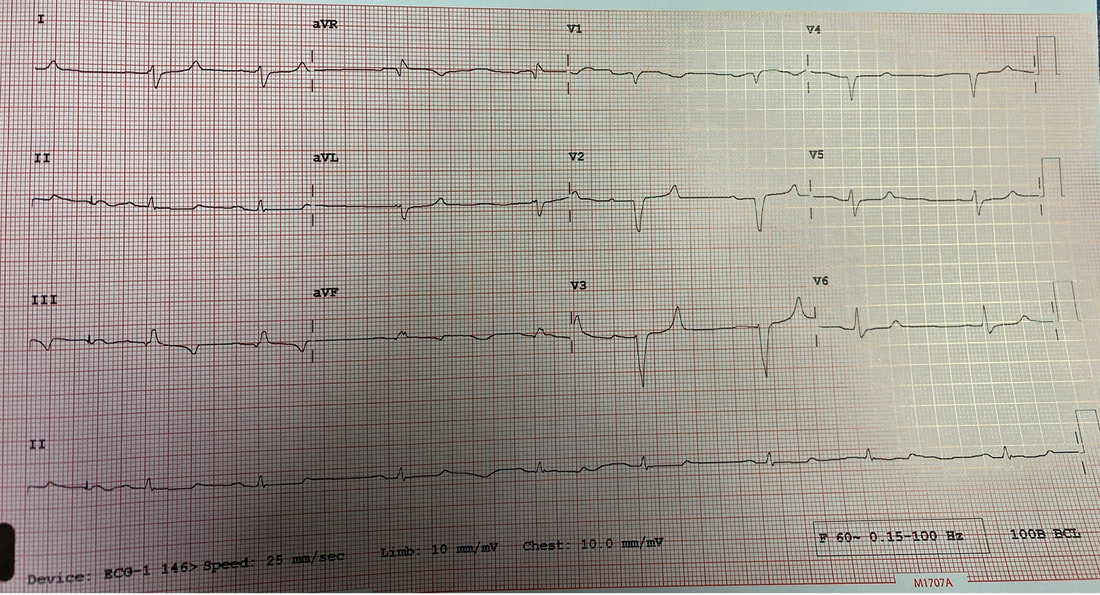

Author: Lisa Di Tomaso, DO PGY-3 Reviewed by: Brian Ault, DO In our residency training, one of the milestones marking the transition from a 2nd year to a 3rd year is the ability to sign EKG’s. EVERY SINGLE EKG performed in the department must be signed by a provider within 10 minutes. And let me tell you. We order A TON of EKGs. 3rd year residents have the…privilege? No. Responsibility of being allowed to sign-off on an EKG. In the last few months of 2nd year we take an EKG exam to prove competency and then the current 3rd years pass the torch. EKGs will randomly be dropped on your desk, waved in your face and you will even by stopped in the hall by the EKG techs needing a signature on the EKG (side note, for this reason, always wear a watch and carry a pen). We are taught that for a STEMI activation you need two things: abnormal EKG and a good story. But sometimes an EKG is so abnormal, so bizarre, I do not care if you came in for toe pain. Case in point: the EKG that got dropped on my desk at 5:25pm on a Tuesday evening. Two other things you should know about our emergency department to give background. One, our shifts end at 6pm. Two, Tuesday night is protected time for conference so there is no resident to sign-out to, only the attending. So here I am trucking along trying to get my notes done and wrap up my last few patients so I can leave on time and make it to our interview meet & greet dinner at 6:30pm. And then, very quietly, this EKG gets slipped onto my desk. The conversation between the EKG tech and myself went something like this: Me: H*** s***! What are they here for? EKG tech: Uh, I think elbow pain? Me: Huh? Okay, never mind. Where are they? EKG tech: I think EMS was taking them up front to triage. I then proceed to speed walk (I try not to run in the ER as people tend to panic) to triage where I find EMS trying to offload a frail and chronically ill appearing, but still currently alive and breathing, female. I quickly avert their efforts and practically drag the poor EMS crew back to the main pod to a monitored bed. The patient was connected to a monitor, defibrillator pads placed and I scrambled back to my computer to throw in orders. I remember very distinctly being taught in lectures that if you see a bizarre EKG that makes you go “h*** s***, WHAT is that?” that you should always think, HYPERKALEMIA. I, like so many other physicians, have neuroses and I was always worried I would miss this diagnosis but alas, my training has indeed prepared me well and OH MY GOSH how could I miss that??? It practically slapped me in the face. Hyperkalemia is defined as a serum potassium greater than 5.5 mEq/L. The most common cause is actually pseudo-hyperkalemia which is caused by a hemolyzed blood sample or leaving a tourniquet on too long during blood draw. True hyperkalemia can be caused by mainly two different groups: redistribution or an increase in total body potassium. Redistribution is when there is a shift in the potassium from the intracellular to extracellular space: think DKA, crush injuries, rhabdomyolysis, electrical burns, tumor lysis syndrome. An increase in total body potassium can be caused by diet, blood transfusions, medications (K+ sparing diuretics yes but also ACE inhibitors, NSAIDs and beta-blockers) and the most frequently encountered acute/chronic renal failure. Our patient had the latter. She was an ESRD patient who unfortunately was well known to our hospital and had missed her last two dialysis sessions. The treatment for hyperkalemia can be simplified into three goals: stabilize the cardiac membrane, shift K+ intracellularly, remove K+ from body. Stabilizing the cardiac membrane is indicated if you have EKG changes or generally if your K+ is greater than 7 mEq/L. EKG changes that you can see are peaked T-waves, prolonged PR interval, shortened QT interval, widened QRS and finally a sine wave pattern. Someone told me once to imagine that the EKG is first being squished and then slowly pulled apart and that has helped me remember the changes well. You have two options for stabilizing the cardiac membrane and both involve calcium. If you have a central line, you give calcium chloride 1 gram over 1-2 minutes as you can see tissue necrosis with extravasation. This is also the formulation of calcium we use in codes because well, they’re already dead and extravasation is the least of their problems. If you’re patient is not coding or you only have peripheral access you give aliquots of 1 gram calcium gluconate until you have normalization of the EKG, up to 15 grams. It is important to note that stabilizing the cardiac membrane only buys you time to fix the hyperkalemia but it does NOT treat hyperkalemia. That comes with the next goal: shift K+ intracellularly, which is the ‘meat and potatoes’ of the treatment. Insulin and albuterol are the two options although in clinical practice, most of give both medications. Insulin is dosed at 10 units regular insulin IV, along with 25-50 grams of glucose if the blood glucose is less than 300mg/dL or unknown. If your patient has the following risk factors: glucose <150 mg/dL, AKI/CKD, no history of diabetes, weight <60kg, female sex, consider decreasing the dose of insulin to 5 units. Albuterol is usually given as a nebulized treatment of 15-20mg. And finally, the last goal of treatment is to remove K+ from the body. This is usually done by the primary admitting team however you should be familiar with the treatments especially given prolonged hold times we are seeing in our emergency departments. IV furosemide dosed at 40-80mg is an option however make sure your patient has adequate urine output first, not an option in the usual culprit: ESRD patients. Then there are two types of potassium binders: sodium polystyrene sulfonate and sodium zirconium cyclosilicate- IMHO the only thing you should know about these is that the use of sodium polystyrene is controversial due to the risk of bowel perforation. If the hyperkalemia is from dehydration, rhabdomyolysis, diabetic ketoacidosis you can treat with IV lactated ringer’s solution for volume expansion. Avoid normal saline due to the hyperchloremic acidosis which shifts K+ OUT of cells, seems counter-productive. Lastly, definitive treatment, and what you will encounter most frequently, is that these patients need emergent dialysis. Probably the one and only indication to wake your friendly neighborhood nephrologist up at 2am. So back to our patient. She was stabilized in the emergency department with 5 units insulin, 15mg albuterol and 2g calcium gluconate. Her repeat EKG showed significant improvement (see below) and she was admitted to the ICU for close monitoring until her dialysis could be performed. All in all, a great shift with a fantastic learning experience. And I still made it to the interview dinner just a mere five minutes late. Maybe I even saw some of you there.

References: Marx, J. A., & Rosen, P. (2014). Rosen's emergency medicine: Concepts and clinical practice (8th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

ABOUT USVegasFOAM is dedicated to sharing cutting edge learning with anyone, anywhere, anytime. We hope to inspire discussion, challenge dogma, and keep readers up to date on the latest in emergency medicine. This site is managed by the residents of Las Vegas’ Emergency Medicine Residency program and we are committed to promoting the FOAMed movement. Archives

June 2022

Categories |

CONTACT US901 Rancho Lane, Ste 135 Las Vegas, NV 89106 P: (702) 383-7885 F: (702) 366-8545 |

ABOUT US |

WHO WE ARE |

WHAT WE DO |

STUDENTS |

RESEARCH |

FOAM BLOG |

© COPYRIGHT 2015. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

LasVegasEMR.com is neither owned nor operated by the Kirk Kerkorian School or Medicine at UNLV . It is financed and managed independently by a group of emergency physicians. This website is not supported financially, technically, or otherwise by UNLVSOM nor by any other governmental entity. The affiliation with Kirk Kekorian School of Medicine at UNLV logo does not imply endorsement or approval of the content contained on these pages.

Icons made by Pixel perfect from www.flaticon.com

Icons made by Pixel perfect from www.flaticon.com

RSS Feed

RSS Feed