|

Author: Quynhvy Ta, DO PGY3

Reviewed by: Jordana Haber, MD, MACM For decades in the U.S. and around the world, maternal mortality rates decreased, due to medical advancements in conjunction with public health efforts. Women gained increasingly healthier living conditions, improved maternity services, greater access to surgical procedures and antibiotics. Then, about 30 years ago, the US maternal mortality ratio began to rise. Between 1990 and 2016, the U.S. was the only high-income country in which material death increased, more than doubling over that time span. In 1987 the rate was 7 per 100k live births. Today it is an astounding 24 per 100k. Not only is the U.S. a stark outlier among our peers but giving birth in the U.S. is paradoxically becoming more dangerous as maternal health is improving around the rest of the world. Pregnancy related mortality and morbidity rates are unacceptably high in this highly developed country. Most of these deaths and health sequela related to childbirth, most disturbingly, are preventable. The maternal mortality ratio is defined as a death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy, irrespective of duration and site of pregnancy, from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management, notably not from accidental or incidental causes. This is the number used by the WHO, a rate of deaths per 100k live births, and the number most cited as an index to examine historical trends. This is a very conservative estimate of what’s really happening, since at least 24% of maternal deaths occur in the postpartum period after 42 days. Pregnancy-related mortality encompasses up to one year postpartum. During pregnancy, hemorrhage and cardiovascular conditions are the leading causes of death. At birth, infection is the leading cause. And in the postpartum period, typically after the traditional 6–8-week post pregnancy visit, cardiomyopathy, and mental health conditions, including substance use and suicide, are identified as leading causes. Severe maternal morbidity is defined as the unexpected outcomes of the process of labor and delivery that result in short- or long-term consequences to a woman's health, most common indicators in the U.S. being blood transfusion, DIC, hysterectomy, acute renal failure, and ARDS. ACOG and the CDC recommend the following two criteria to screen for severe maternal morbidity: transfusion of four or more units of blood, and admission of a pregnant or postpartum woman to an ICU. Akin to the cases of maternal mortality, the outcomes that are encompassed by maternal morbidity could have largely been avoided with timely and appropriate care. The US currently ranks 55th in the world behind all other developed nations in maternal mortality. Russia is currently ranked 52nd. The maternal mortality rate in the US is 23.8 per 100k live births, a stark contrast to the 3 per 100k in New Zealand, Norway, and the Netherlands. This rate is more than doubled, 55 per 100k, for Black women. It should be noted that these numbers do not account for undocumented pregnant women. Severe maternal morbidity affects approximately 60 thousand women annually- and this is a conservative estimate. According to a report from maternal mortality review committees across 14 states, two thirds of pregnancy related deaths were preventable. Both patient and health systems factors were noted to profoundly contribute to these abysmal numbers. Reproductive factors including younger age, higher parity, and unwanted pregnancy are associated with higher mortality. On a health system level, there is a lack of standardized approaches to emergency obstetric care. Depending on the primary provider, there exists great variability in the approach to the management of severe hypertension, VTE, obstetric hemorrhages. There is a marked lack of health services, including lack of access, providers, preventative services, and notably postpartum care, when most maternal deaths occur. The disparate access to quality, accessible and culturally appropriate health care is undoubtedly a driving factor in the gaping racial disparities in maternal health outcomes. Unequal access to providers, education, structural racism and sexism, avoidance of healthcare facilities due to a history of racism, and a lack of empathy from healthcare providers are just a handful of the socioeconomic injustices that exacerbate this crisis. There are some notable distinctions of the U.S., compared to other high-income countries, that should be mentioned. We are the only high-income country that does not guarantee paid leave time from work (while several provide more than a year.) We have the lowest overall supply of midwives and OB/GYNs, 15 to every 1000 births which is less than half of all other high-income countries. We are also the only country not to guarantee access to provider home visits in the postpartum period. Women with Medicaid coverage, as compared to those with private health insurance, are more likely to report no postpartum visit, having to return to work within 2 months of birth, less postpartum support at home, not having decision autonomy during labor and delivery, and being treated unfairly and with disrespect by providers. The Black white maternal mortality disparity is the largest amongst health disparities. Social determinants of health including disparities in income, housing, and education associated with poorer health and chronic conditions put Black women at greater risk. They are at greater risk of dying from pregnancy related hemorrhage, hypertensive disorders, and cardiomyopathy. Racism in healthcare, at an individual level, compounds this issue, with studies demonstrating that Black women are less likely to have access to treatment and receive good quality care even with insurance coverage. Though there is no statistically significant greater prevalence of pre-eclampsia or placental abruption among Black women, they are three times more likely to die from these conditions, independent of age, parity or education. At the intersection of sexism and racism, women of color are not listened to or respected by their health care providers, often receiving delayed diagnosis or care. A Black mother with a college education is 60% more likely to die from a white or Hispanic woman with less than a high school education. Access to safe abortion care is an essential component of maternal health care. Per the CDC, carrying a pregnancy to term is thirty three times deadlier than having an abortion, the latter with a 0.6 maternal mortality rate per 100 thousand. Women most likely to seek abortion care, i.e., women of color, those with poor access to care and those with chronic conditions, are those most likely to encounter serious complication during pregnancy. According to a University of Colorado study in 2021, banning abortion nationwide would lead to a 21% increase in number of pregnancy related deaths overall and a 33% increase among black women. Improving maternal health requires identifying and addressing barriers that limit access to quality maternal health services at systemic and individual levels. We most prevent unwanted pregnancies, providing all women including adolescents access to contraception, safe abortion services and quality post abortion care. We must improve women’s health services before, during, and after pregnancy. We need to increase not only first trimester entry into prenatal care, but to maintain postpartum care. The diversity of causes of maternal mortality and morbidity that occur at different stages of pregnancy until one year postpartum must be addressed through integrated care delivery models such as tele-health, midwives and doulas. There needs to be a greater availability of maternal health services, particularly in underserved areas. Paid parental leave, that is actually taken by parents and accepted culturally, should be guaranteed. We must ensure nondiscrimination in access to health care by supporting vulnerable segments of our population, particularly Black women who need more access to comprehensive public health programs that address pre-conceptual health and chronic conditions, implicit racial bias among healthcare professionals, and improving the quality of care at the hospitals predominantly servicing these women at the community level. And we must standardize care through implementing evidence-based practices by developing safety bundles addressing obstetric emergencies such as obstetric hemorrhage, severe, HTN, venous thromboembolism. Maternal mortality and morbidity are largely preventable. It is unacceptable that these rates have markedly increased over the last two decades despite the marked medical advancements made in that same time span. It is our duty as health care providers to incorporate this knowledge into our own practice and relationships with patients in our current landscape, in which political galvanization seems to be eroding trust in medical expertise. We must not only practice health care, but advocate for the fundamental right to health. References:

0 Comments

Author: Quynhvy Ta, DO PGY3

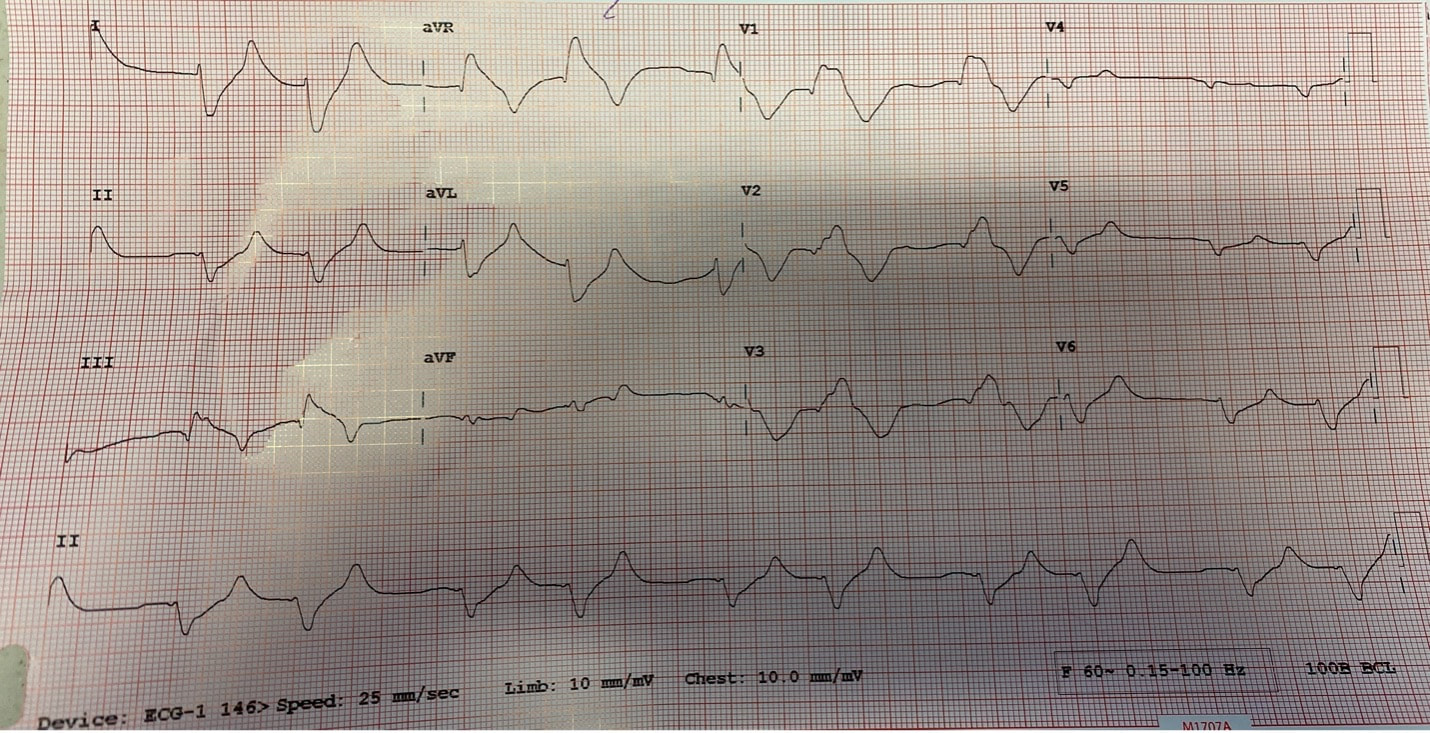

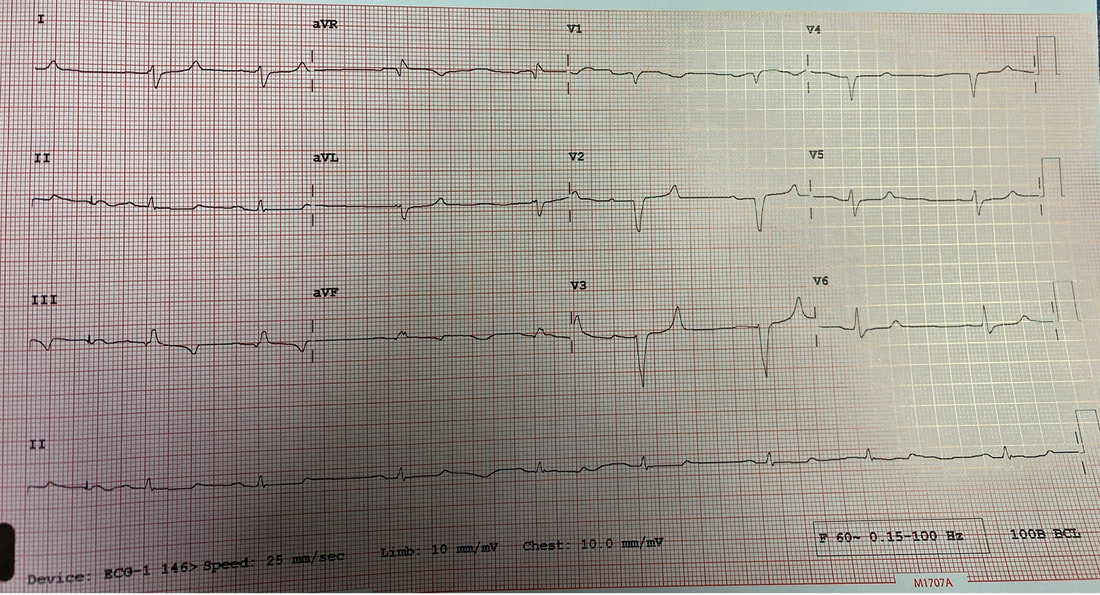

Reviewed by: Jordana Haber, MD, MACM In the 5th grade, I had an excused absence signed by my parents allowing me to skip “sex-ed” day. Instead, I spent the day in the company of my classmate Jenny, one of the fellow offspring of similarly well-meaning but “sex is bad” dogma brainwashed parents, who told me that even a microscopic droplet of a boy’s pee left on the toilet seat could crawl into my belly and grow into a baby. Petrified, I squatted on every public toilet seat for at least the next two years of my naive, internet-illiterate and sex-ed deprived adolescence. At 16, I was persistent to spend part of my summer break volunteering at abortion clinics, finding this the most compelling part of the healthcare field. The only planned parenthood in town did not take underage volunteers. I subsequently went to at least a dozen “pregnancy crisis centers” under the assumption they were legitimate medical clinics, only to be met with a dark dose of reality embodied by the mound of scripture and propaganda laden lectures I had acquired, in lieu of any reproductive healthcare acumen. During freshman year of college, I started taking oral contraceptives. I came home one weekend to get my wisdom teeth extracted. My dad, and the entire waiting room populace, were abruptly and loudly informed of this by the clerk reviewing my pre-op paperwork. Sticking her head out of the glass framed receptacle, she queried if it was true (as I had indicated quite clearly on the written form!) that I was on birth control, her tone suggesting this must be some sort of grave mistake. Why this fact was even relevant at all remains a mystery to me to this day, despite being just a couple months shy of completing my medical residency. Let’s fast forward to medical school, during which I was the treasurer of the medical students for choice club and found myself subjugated to the aggressively closed-minded whims of some members of an administration who I felt, at every turn, undermined any activities they determined to be “too political.” Handing out condoms, as it turns out, was not in the scope of healthcare, but deemed to be a radical act outside of our lane. My intern residency class (made up of 7 women and 3 men) stood in contrast to the legacy immediately preceding us, when the program of thirty residents were entirely male save two women. When we composed a brief statement for our social media pages expressing our solidarity with the BLM movement in the wake of George Floyd’s murder, it was opposed by a small but very loud minority that felt it was, again, “too political.” This was unsurprising, but it was the silence, and perhaps general apathy, of the others that hurt. At their graduation party I later heard they were apparently teased for being “me too’d” by us. There were, of course, exceptions to this. The Diversity, Inclusion, Community and Equity committee was formed under the guidance of my faculty mentor and our chief resident. Our program’s application process was extensively reviewed, and modifications were made accordingly in order to reflect the importance of representation and diversity in our program. Maintaining a monthly health equity lecture series is just the beginning to insure we reserve space and lend attention to these topics. I’m a third year now and I am happy to be in a group of co-residents that no longer looks identical to the hair dye meme of indistinguishable white dudes. In time, my anger and sadness about the situation was replaced by the inconvenient stressors of residency and of life in general (also a global pandemic). Time, in conjunction with my predisposition for self-doubt and, perhaps, a general lack of courage or clarity, I chose to suppress my often “too political” inclinations, largely choosing politeness in the name of peace. I don’t think it’s by chance that I never arranged for a guest lecture, or wrote one myself, on the topic of abortion. Maybe, I thought, it might be “too political.” In the days following the leaked Roe v Wade decision, I found myself in the depths of a hypomanic daze, insufficiently prepared for a verdict that I’d read countless times was coming. Doom scrolling reddit and twitter to fuel my sadness and anger, mitigating my guilt for being surprised by the outcome by listening to every relevant podcast and watching every documentary and reading every think piece from OB/GYNs and historians and lawyers I could squeeze into my waking hours, poring through medical papers in search of any actionable solutions via medical management in the ED, I was consumed by my own feelings of helplessness. I was desperate to find ways in which I could exercise control as I simultaneously felt my own autonomy as a woman being imminently taken away from me. During my psychiatry rotation as an MS3, l sat in on the psychotherapy session of a Vietnam War veteran suffering from PTSD, during which he broke down in his own conclusion that all his fighting was ultimately for nothing. I remember telling him afterwards that, in fact, both my parents are Vietnamese American refugees. His eyes swelled with tears when I told him that I was going be a doctor, and that I, for one, did not feel like it was for nothing. The profound sense of connection to someone so incredibly far away from my life experience, yet so intertwined in my own destiny, resonates with me still. It was one of the most poignant moments of my medical experiences to this day, and the subsequent gratitude I felt was something I try and remind myself of often. I grew up in the suburbs of southern California, wanting for nothing, am the daughter of two incredibly loving and always well-meaning first generation Vietnamese American refugee parents- who gave up everything to come here. I had tutors and money and plenty of time- that’s why I got to achieve my childhood dream of being a doctor. I am the recipient of immense privileges- my education, my financial security, my sexual preferences, my zip code, my supportive partner, friends, family, and mentors to name a few, rendering the decision to overturn Roe v. Wade a largely ideological attack. For now, that is. The same judgment and resentment I had towards my seniors for their perceived complacency could just as fairly be directed towards my own inaction and willful ignorance. The path of least resistance is easy. Polite omission of treading anything “too political” is actually cowardice, guised conveniently as “professionalism.” Our profession is to care for the health of others, to advocate for those that are most vulnerable, who have nowhere else to turn but our ED because of systemic failures in our society. Gun violence, environmental injustices, racial and socioeconomic disparities, reproductive rights, and abortion- these topics ARE healthcare. I am crazy lucky to be in a position where I can, as a “professional,” advocate for the people most vulnerable to these systemic injustices that too often end up in the emergency department. As a woman, I am enraged by the continued attacks on our bodily autonomy. As a 2nd generation Vietnamese American, raised on model minority rhetoric and that romantic narrative of the American dream, I am devastated by the implications of this likely SCOTUS decision. As an emergency medicine physician, I will fight for autonomy, reproductive justice, and defend the fundamental human right to make decisions about our bodies and our destinies. Author: Lisa Di Tomaso, DO PGY-3 Reviewed by: Brian Ault, DO In our residency training, one of the milestones marking the transition from a 2nd year to a 3rd year is the ability to sign EKG’s. EVERY SINGLE EKG performed in the department must be signed by a provider within 10 minutes. And let me tell you. We order A TON of EKGs. 3rd year residents have the…privilege? No. Responsibility of being allowed to sign-off on an EKG. In the last few months of 2nd year we take an EKG exam to prove competency and then the current 3rd years pass the torch. EKGs will randomly be dropped on your desk, waved in your face and you will even by stopped in the hall by the EKG techs needing a signature on the EKG (side note, for this reason, always wear a watch and carry a pen). We are taught that for a STEMI activation you need two things: abnormal EKG and a good story. But sometimes an EKG is so abnormal, so bizarre, I do not care if you came in for toe pain. Case in point: the EKG that got dropped on my desk at 5:25pm on a Tuesday evening. Two other things you should know about our emergency department to give background. One, our shifts end at 6pm. Two, Tuesday night is protected time for conference so there is no resident to sign-out to, only the attending. So here I am trucking along trying to get my notes done and wrap up my last few patients so I can leave on time and make it to our interview meet & greet dinner at 6:30pm. And then, very quietly, this EKG gets slipped onto my desk. The conversation between the EKG tech and myself went something like this: Me: H*** s***! What are they here for? EKG tech: Uh, I think elbow pain? Me: Huh? Okay, never mind. Where are they? EKG tech: I think EMS was taking them up front to triage. I then proceed to speed walk (I try not to run in the ER as people tend to panic) to triage where I find EMS trying to offload a frail and chronically ill appearing, but still currently alive and breathing, female. I quickly avert their efforts and practically drag the poor EMS crew back to the main pod to a monitored bed. The patient was connected to a monitor, defibrillator pads placed and I scrambled back to my computer to throw in orders. I remember very distinctly being taught in lectures that if you see a bizarre EKG that makes you go “h*** s***, WHAT is that?” that you should always think, HYPERKALEMIA. I, like so many other physicians, have neuroses and I was always worried I would miss this diagnosis but alas, my training has indeed prepared me well and OH MY GOSH how could I miss that??? It practically slapped me in the face. Hyperkalemia is defined as a serum potassium greater than 5.5 mEq/L. The most common cause is actually pseudo-hyperkalemia which is caused by a hemolyzed blood sample or leaving a tourniquet on too long during blood draw. True hyperkalemia can be caused by mainly two different groups: redistribution or an increase in total body potassium. Redistribution is when there is a shift in the potassium from the intracellular to extracellular space: think DKA, crush injuries, rhabdomyolysis, electrical burns, tumor lysis syndrome. An increase in total body potassium can be caused by diet, blood transfusions, medications (K+ sparing diuretics yes but also ACE inhibitors, NSAIDs and beta-blockers) and the most frequently encountered acute/chronic renal failure. Our patient had the latter. She was an ESRD patient who unfortunately was well known to our hospital and had missed her last two dialysis sessions. The treatment for hyperkalemia can be simplified into three goals: stabilize the cardiac membrane, shift K+ intracellularly, remove K+ from body. Stabilizing the cardiac membrane is indicated if you have EKG changes or generally if your K+ is greater than 7 mEq/L. EKG changes that you can see are peaked T-waves, prolonged PR interval, shortened QT interval, widened QRS and finally a sine wave pattern. Someone told me once to imagine that the EKG is first being squished and then slowly pulled apart and that has helped me remember the changes well. You have two options for stabilizing the cardiac membrane and both involve calcium. If you have a central line, you give calcium chloride 1 gram over 1-2 minutes as you can see tissue necrosis with extravasation. This is also the formulation of calcium we use in codes because well, they’re already dead and extravasation is the least of their problems. If you’re patient is not coding or you only have peripheral access you give aliquots of 1 gram calcium gluconate until you have normalization of the EKG, up to 15 grams. It is important to note that stabilizing the cardiac membrane only buys you time to fix the hyperkalemia but it does NOT treat hyperkalemia. That comes with the next goal: shift K+ intracellularly, which is the ‘meat and potatoes’ of the treatment. Insulin and albuterol are the two options although in clinical practice, most of give both medications. Insulin is dosed at 10 units regular insulin IV, along with 25-50 grams of glucose if the blood glucose is less than 300mg/dL or unknown. If your patient has the following risk factors: glucose <150 mg/dL, AKI/CKD, no history of diabetes, weight <60kg, female sex, consider decreasing the dose of insulin to 5 units. Albuterol is usually given as a nebulized treatment of 15-20mg. And finally, the last goal of treatment is to remove K+ from the body. This is usually done by the primary admitting team however you should be familiar with the treatments especially given prolonged hold times we are seeing in our emergency departments. IV furosemide dosed at 40-80mg is an option however make sure your patient has adequate urine output first, not an option in the usual culprit: ESRD patients. Then there are two types of potassium binders: sodium polystyrene sulfonate and sodium zirconium cyclosilicate- IMHO the only thing you should know about these is that the use of sodium polystyrene is controversial due to the risk of bowel perforation. If the hyperkalemia is from dehydration, rhabdomyolysis, diabetic ketoacidosis you can treat with IV lactated ringer’s solution for volume expansion. Avoid normal saline due to the hyperchloremic acidosis which shifts K+ OUT of cells, seems counter-productive. Lastly, definitive treatment, and what you will encounter most frequently, is that these patients need emergent dialysis. Probably the one and only indication to wake your friendly neighborhood nephrologist up at 2am. So back to our patient. She was stabilized in the emergency department with 5 units insulin, 15mg albuterol and 2g calcium gluconate. Her repeat EKG showed significant improvement (see below) and she was admitted to the ICU for close monitoring until her dialysis could be performed. All in all, a great shift with a fantastic learning experience. And I still made it to the interview dinner just a mere five minutes late. Maybe I even saw some of you there.

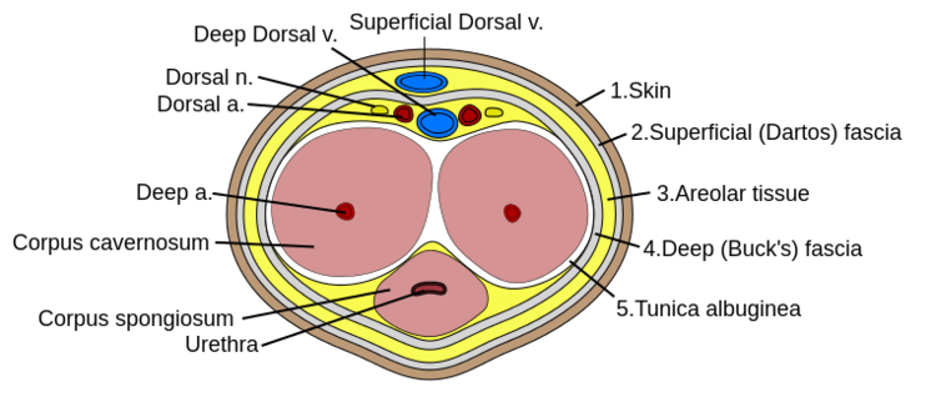

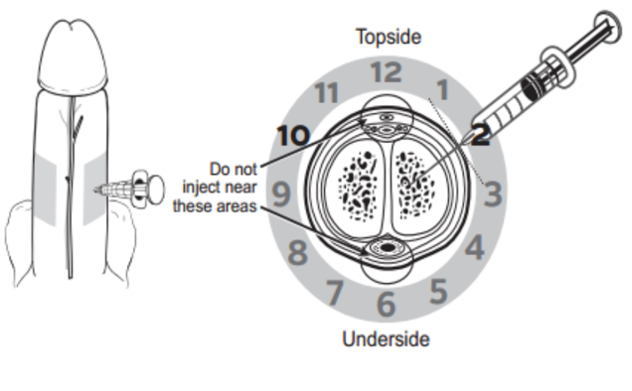

References: Marx, J. A., & Rosen, P. (2014). Rosen's emergency medicine: Concepts and clinical practice (8th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders. Author: Lisa Di Tomaso, DO PGY-3 Reviewed by: James Bailey, MD Introduction: Priapism is defined as a sustained erection lasting longer than 4 hours that is not associated with sexual stimulation. It can lead to penile necrosis and erectile dysfunction with the risk increasing after 24 hours. Between 2006 and 2009 approximately 32,000 visits were for priapism, an incidence of 5.3 per 100,000 males per year. The incidence increased by 31% during summer months, likely due to an increase in trauma which is a known cause. Pathophysiology: Before getting into the pathology of priapism, it’s important to review a little bit of anatomy. The corpus cavernosum are twin parallel structures that fill with blood to achieve an erection. The veins run on the dorsal aspect in the midline and the urethra, surrounded by corpus spongiosum, runs along the medial ventral aspect. There are two types of priapism, high-flow also called non-ischemic, and low flow or ischemic priapism. High-flow (non-ischemic) priapism is typically caused by injury either to the perineum with a straddle injury or to the spinal cord. High-flow priapism is usually painless and a blood sample from the corpus cavernosum will be arterial in appearance and on blood gas analysis. The assumed mechanism for a spinal cord injury is the abrupt loss of sympathetic output to pelvic vasculature leads to increased parasympathetic output and thus uncontrolled arterial flow into penis. Injuries to the perineum, usually a straddle type injury, can cause an arterio-cavernosal shunt leading to increased arterial inflow. Low-flow priapism is more common and is a urologic emergency as it can cause penile necrosis and erectile dysfunction. Unlike high-flow, it is painful and usually the shaft is hard while the glans is soft. It is caused by some sort of veno-occlusion which leads to pooling of deoxygenated blood in cavernosal tissues. The pooling of deoxygenated blood can prevent further arterial inflow leading to tissue ischemia and necrosis if not treated and sexual dysfunction if intervention is not performed in time. It can be caused by hematologic disorders such as leukemia or sickle cell disease, DIC, pelvic malignancy or drugs, both prescription and illicit. Common prescription triggers include anti-depressants particularly SSRI’s and trazadone, anti-psychotics and cocaine is a well-known trigger from illicit substances. It is also worth noting that erectile dysfunction medications like sildenafil (Viagra) can cause a priapism if the intended erection for sexual intercourse does not resolve after 4 hours. Management: The management depends on the type of priapism. High-flow (non-ischemic) priapism is managed by treating the underlying cause. It usually self-resolves without intervention and does not cause ischemia or sexual dysfunction. Low-flow (ischemic) priapism can be managed in a step-wise approach. Don’t forget pain control if needed for patient comfort or cooperation which can be achieved with narcotics or a penile nerve block. A penile nerve block is performed by local infiltration of anesthetic with a 27g needle at the base of the penis at the 2/3 o’clock and 9/10 o’clock positions or as a ring block to target the dorsal nerves. As the penile vasculature runs in the midline, be sure to aspirate before injecting and stay lateral to prevent an incidental intravenous injection of the anesthetic. The steps involved in management of low-flow priapism can be remembered as below: 1.Aspirate 25mL from cavernosum, 2x 2.Irrigate cavernosum with 25mL of cold saline 3.Medication injection 4.Wrap in elastic bandage after detumescent achieved 5.Consult if Refractory --> urology for shunt procedure Before choosing to aspirate be sure the patient is a candidate and would benefit. If the priapism has been present longer than 48 hours there is rare benefit and there is a high risk of impotence even with treatment. If your patient is an appropriate candidate then it is safe to proceed. Be sure to obtain informed consent and then prep the penis with chlorhexidine and drape appropriately. If a penile nerve block had not been previously performed, you could choose to do one now or inject local anesthetic at aspiration site. Similar to aspiration you will insert an 18g needle into the shaft at the 2/3 o’clock and 9/10 o’clock positions and aspirate about 20-30cc of blood from each side. If choosing to proceed to injection or irrigation, you can leave the needle in place at this step. For irrigation you will irrigate each side of the cavernosum with 20-30mL of cold saline. If detumescence has still not been achieved than you can proceed with medication injection. In adult patients the drug of choice is phenylephrine and epinephrine has been shown to be more effective in the pediatric population. You will first need to dilute 1mL of the phenylephrine 1mg/mL in a 9mL normal saline flush for a final concentration of 100mcg/mL. This is the same process as making a push-dose epinephrine. At a phenylephrine concentration of 100mcg/mL you will inject 100-200mcg (1-2mL) every 3-5 minutes with a maximum dosage of 1000mcg (10mL) until detumescence has been achieved or one hour has elapsed. Before injecting phenylephrine make sure the patient is on the cardiac monitor and watch for reflex bradycardia, use caution in patients with cardiovascular disease. Unlike aspiration you only need to inject one side as the channel between the cavernosa is sufficient to treat both sides. If all efforts have failed, you can try wrapping the penis in an elastic bandage or having the patient run in place or do squats.

If the patient has sickle cell disease treatment should also be aimed at treating the underlying cause with IV fluids, pain control and supplemental oxygen. You can also consider transfusion for a goal hematocrit of >30%. Disposition: Disposition depends on the underlying cause and success of treatment. If the priapism is high-flow the disposition will depend on the management of the underlying cause but will usually be admission for the inciting trauma. If the low-flow priapism was successfully treated in the emergency department and detumescence was achieved, then the patient can be safely discharged with outpatient urology follow-up. Be sure to give counseling on avoidance of using ED medications or illicit substances if this was found to be the cause. If all the above methods of management failed and the patient still has a priapism, then an emergent consult to urology is necessary for likely urology or interventional radiology intervention. References: Roghmann F, Becker A, Sammon JD, Ouerghi M, Sun M, Sukumar S, Djahangirian O, Zorn KC, Ghani KR, Gandaglia G, Menon M, Karakiewicz P, Noldus J, Trinh QD. Incidence of priapism in emergency departments in the United States. J Urol. 2013 Oct;190(4):1275-80. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.03.118. Epub 2013 Apr 9. PMID: 23583536. Rosen's Emergency Medicine : Concepts and Clinical Practice. St. Louis :Mosby, 2002. Quarles A, Ogele E, Quigley M(2017, July 4). Priapism: The ED Focused Appropach. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary By Bennett N]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/priapism |

ABOUT USVegasFOAM is dedicated to sharing cutting edge learning with anyone, anywhere, anytime. We hope to inspire discussion, challenge dogma, and keep readers up to date on the latest in emergency medicine. This site is managed by the residents of Las Vegas’ Emergency Medicine Residency program and we are committed to promoting the FOAMed movement. Archives

June 2022

Categories |

CONTACT US901 Rancho Lane, Ste 135 Las Vegas, NV 89106 P: (702) 383-7885 F: (702) 366-8545 |

ABOUT US |

WHO WE ARE |

WHAT WE DO |

STUDENTS |

RESEARCH |

FOAM BLOG |

© COPYRIGHT 2015. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

LasVegasEMR.com is neither owned nor operated by the Kirk Kerkorian School or Medicine at UNLV . It is financed and managed independently by a group of emergency physicians. This website is not supported financially, technically, or otherwise by UNLVSOM nor by any other governmental entity. The affiliation with Kirk Kekorian School of Medicine at UNLV logo does not imply endorsement or approval of the content contained on these pages.

Icons made by Pixel perfect from www.flaticon.com

Icons made by Pixel perfect from www.flaticon.com

RSS Feed

RSS Feed