|

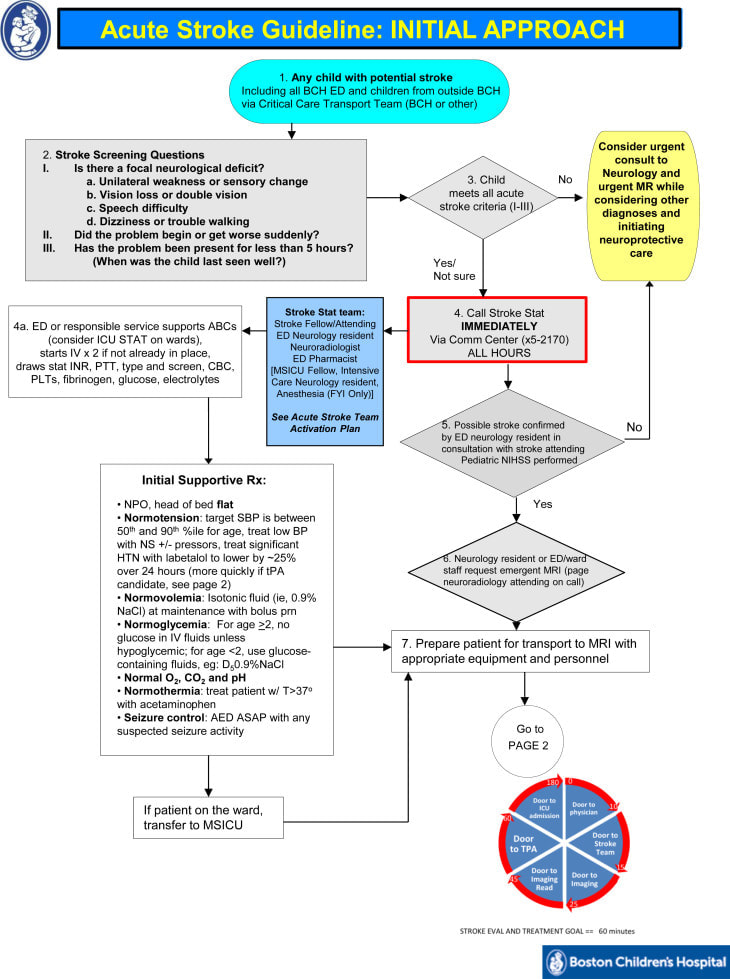

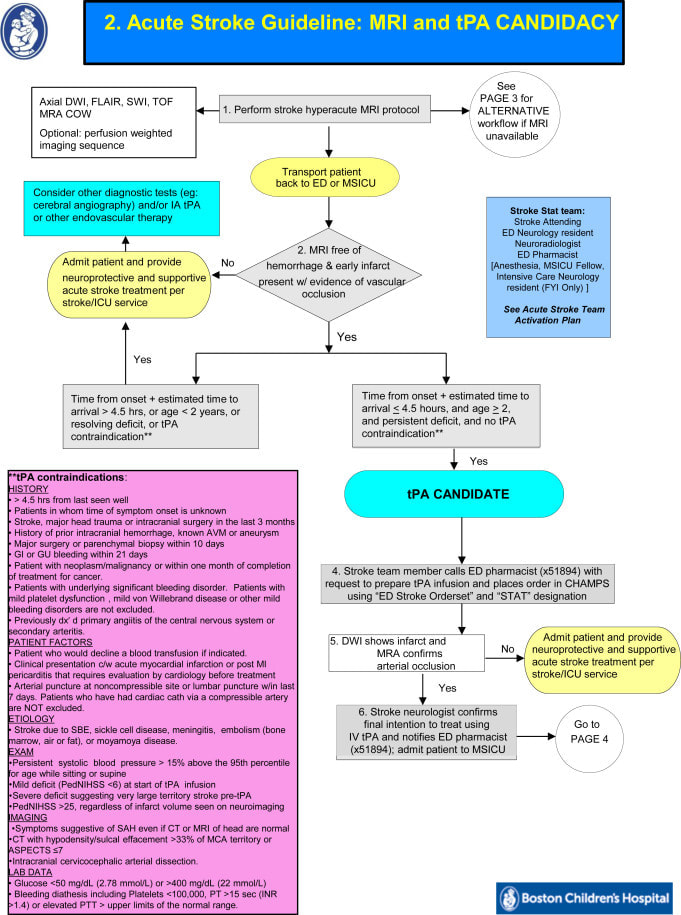

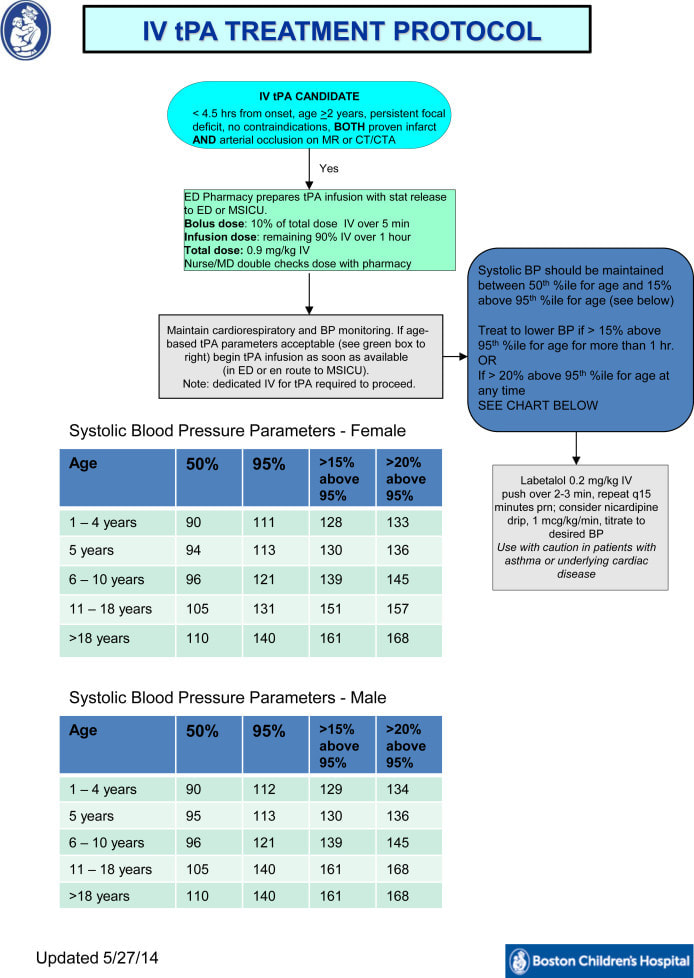

By Elizabeth Chen MD PGY-3 Acute Ischemic Stroke (AIS) in the pediatric population is extremely rare, has many mimics, and often presents with signs and symptoms that differ from a typical “adult” stroke. Because the goal for diagnosis and treatment of AIS in adults is 4 hours, these differences often lead to delayed recognition and treatment. In a Canadian study, median interval from time of onset to diagnosis was 22.7 hours. When a stroke occurred in hospital, it still took 12.7 hours to diagnose. When a child had a stroke out of the hospital, it took on average 1.7 hours for patients to present to the hospital, indicating that the time delay to diagnosis was often on the part of the medical staff. Currently, only a handful of large, dedicated pediatric centers have pediatric stroke teams similar to the typical adult “code stroke” teams found in most communities. These pediatric teams are equipped to diagnosis and potentially treat children with AIS quickly but most hospitals are not. The key to improve care for children in the community is for all emergency physicians to be well trained on how to recognize and evaluate children for stroke. Recent estimate of the incidence of pediatric stroke is 2-13 per 100,000 children per year. Presentation in children less than a year old, may show up as focal weakness, but more likely to present as seizures and altered mental status. In older children, it is somewhat more similar to adults with hemiparesis or other focal neurologic signs like aphasia, visual disturbances, or cerebellar signs. According to the International Pediatric Stroke study, half of children with AIS have at least one predisposing factor. In 676 children from ages 29 days to 18 years with AIS, 9% had no risk factors, 53% had arteriopathies, 31% cardiac disorders, and 24% infection. When assessing patients for stroke, have a higher clinical suspicion when they have any of the following risk factors: Arteriopathies: Focal cerebral arteriopathy of childhood—unilateral focal or segmental stenosis of distal carotid arteries and proximal circle of Willis vessels. The cause is unknown but some have had antecedent viral infections which may potentially cause an inflammation vasculitis. Postvaricella arteriopathy—Accounts for nearly 1/3 of childhood AIS. Intraneuronal migration from trigeminal ganglion to cerebral arteries. In a study in Canada with children 6 months to 10 years with confirmed AIS, 31% had Varicella in the preceding year with a mean interval from varicella infection to AIS being 5.2 months. Patients may experience recurrent varicella associated AIS up to 33 weeks after presentations even with antithrombic prophylaxis. Moyamoya—a disease process that causes progressive stenosis of the distal intracranial internal carotid artery, and less commonly stenosis of the anterior cerebral artery, middle cerebral artery , basilar artery, and posterior cerebral artery. Peak incidence is at 5 years. Recurrent TIA/AIS are common. Typically, the strokes are ischemic in childhood and then convert to hemorrhagic strokes in young adulthood. Cervicocephalic arterial dissection—Cervicocephalic arterial dissection accounts for 7.5% of all AIS, half of which are due to trauma. Predisposing factors include trauma, connective tissue abnormalities, fibromuscular dysplasia, and anatomic variations. The cause of intracranial dissection is often spontaneous, while extracranial dissections are associated with trauma. This condition presents with headache, vomiting, dizziness, vertigo, diplopia, confusion, neck pain, and recurrent TIA’s. Sickle Cell Disease (SCD)—These children are at a very high risk of stroke. Approximately 11% of SCD patients will have had a clinically significant stroke by age 20, and this increases to 24% by age 45. Transcranial doppler is important in predicting risk for stroke; a mean velocity greater than 170 cm/sec places patients at a marginal risk, while values greater than 200 cm/sec in MC/ICA are highly associated with increased AIS risk. If a patient with SCD presents with AIS, immediately order transfusion therapy and immediate exchange transfusion for a goal of a HbS fraction less than 30% and a hemoglobin level of 10. Hydroxyurea used by patients with sickle cell disease to reduce the incidence of painful crisis and blood transfusions unfortunately does not prevent stroke recurrence. Congenital heart disease: Stroke is associated with most types of cardiac lesions but complex congenital heart lesions with right to left shunting and cyanosis are particularly prone to cause stroke. Additionally valvular disease, endocarditis, and arrythmias can lead to stroke. Chronic hypoxia leads to a markedly elevated hematocrit which places patients at higher risk for cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. Although the presence of a PFO increases the risk of stroke, it’s presence should not exclude further investigation into other cardiac abnormalities. Hypercoagulable disorders: Prothrombotic states alone are rarely a cause of AIS; however, combined with other mechanisms such as protein C deficiency, antiphospholipid antibodies, and elevated lipoprotein, the odds ratio increases. Vasculitis: Primary vasculitides include Takayasu, giant cell arteritis, polyarteritis nodosa, Kawasaki disease, and primary angiitis of the CNS. Diseases associated with secondary vasculitides include infection (bacterial meningitis, HIV, varicella, syphilis, fungal infections, CNS tuberculosis), malignancy, and collagen vascular diseases. Metabolic: Conditions such as Fabry disease, homocystinuria, and Menkes disease affect the cerebral vessel walls and increase the risk of AIS. Presentation: Infants and toddlers may present with headaches, seizures, altered mental status, behavioral/personality changes, sleepiness or decreased level of consciousness. While older children may present more similarly to adults with severe/sudden headache with vomiting and drowsiness, Vision loss/double vision, severe intractable dizziness, loss of balance/coordination, seizures on one side of the body, numbness/weakness on one side of body, difficulty speaking/understanding others. There are also many stroke mimics in pediatrics that can make the diagnosis difficult. Stroke Mimics n=287 Children (Mackay, Stroke 2017) Migraine-28% Febrile/Afebrile Seizure-15% Bell’s Palsy-10% Stroke-7% Conversion Disorder-6% Syncope-5% Headache NOS-4% Other CNS conditions-10% Diagnosis: Because of the difficulty of making the ultimate diagnosis of AIS in children an MRI and MRA of the brain and neck must be done, after an initial CT. This often increases the time to diagnosis because of the logistics required to provide sedation for an MRI. Management: The goal of treating children with AIS is to minimize morbidity and mortality and if possible to improve perfusion to the ischemic areas of the brain. The system for adults is well organized and shown to improve outcomes. Thrombolysis (tPA) is well documented for use in adults, however it is not FDA approved for anyone under 18 years of age. Attempts have been made to show efficacy and safety in children. There was a large NIH funded study started in 2015, Thrombolysis in Pediatric Stroke Study (TIPS). It was an international multicenter study with a total of 17 different sites. A total of 93 patients were screened; 43 had a confirmed stroke, but only 1 child was enrolled. Almost half the stroke patients did not meet enrollment criteria because of missing the time limit (4.5 hours) to receive tPA. The study was discontinued because of a lack of enrollment. Although there are still no large scale trials showing efficacy and safety there are some case reports showing positive results of tPA in teenage patients. Therefore, management to date should include rapid diagnosis and stabilization to minimize morbidity. Thrombolysis should be considered on a case-by-case basis. Future of AIS evaluation in children: We need to improve awareness of stroke signs and symptoms in pediatric patients in order to diagnose and transport more quickly to a Pediatric Stroke Center. Here is an example of a pediatric stroke evaluation protocol from Boston Children's Hospital: References

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

ABOUT USVegasFOAM is dedicated to sharing cutting edge learning with anyone, anywhere, anytime. We hope to inspire discussion, challenge dogma, and keep readers up to date on the latest in emergency medicine. This site is managed by the residents of Las Vegas’ Emergency Medicine Residency program and we are committed to promoting the FOAMed movement. Archives

June 2022

Categories |

CONTACT US901 Rancho Lane, Ste 135 Las Vegas, NV 89106 P: (702) 383-7885 F: (702) 366-8545 |

ABOUT US |

WHO WE ARE |

WHAT WE DO |

STUDENTS |

RESEARCH |

FOAM BLOG |

© COPYRIGHT 2015. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

LasVegasEMR.com is neither owned nor operated by the Kirk Kerkorian School or Medicine at UNLV . It is financed and managed independently by a group of emergency physicians. This website is not supported financially, technically, or otherwise by UNLVSOM nor by any other governmental entity. The affiliation with Kirk Kekorian School of Medicine at UNLV logo does not imply endorsement or approval of the content contained on these pages.

Icons made by Pixel perfect from www.flaticon.com

Icons made by Pixel perfect from www.flaticon.com

RSS Feed

RSS Feed